Ideas and Ingredients

What does good participation look like?

There have been lots of words written about people’s participation in our society of one person one vote. One of the most well-known is perhaps Sherry Arnstein’s ladder of participation from 1969. It is a way of thinking about the depth of people’s participation in government, and the ladder implies climbing to the higher forms of participation.

The lower of the three zones represents government doing things to citizens where the power lies mainly with selected consultants and pollsters. The middle zone is where government does things for citizens, where the power lies mainly with staff hired to deliver a pre-determined programme. The top zone is where government does things with its citizens, and the power lies with communities.

Think of an organisation you’re familiar with. How high up the ladder would they be?

Arnstein (1969) Ladder of citizen participation

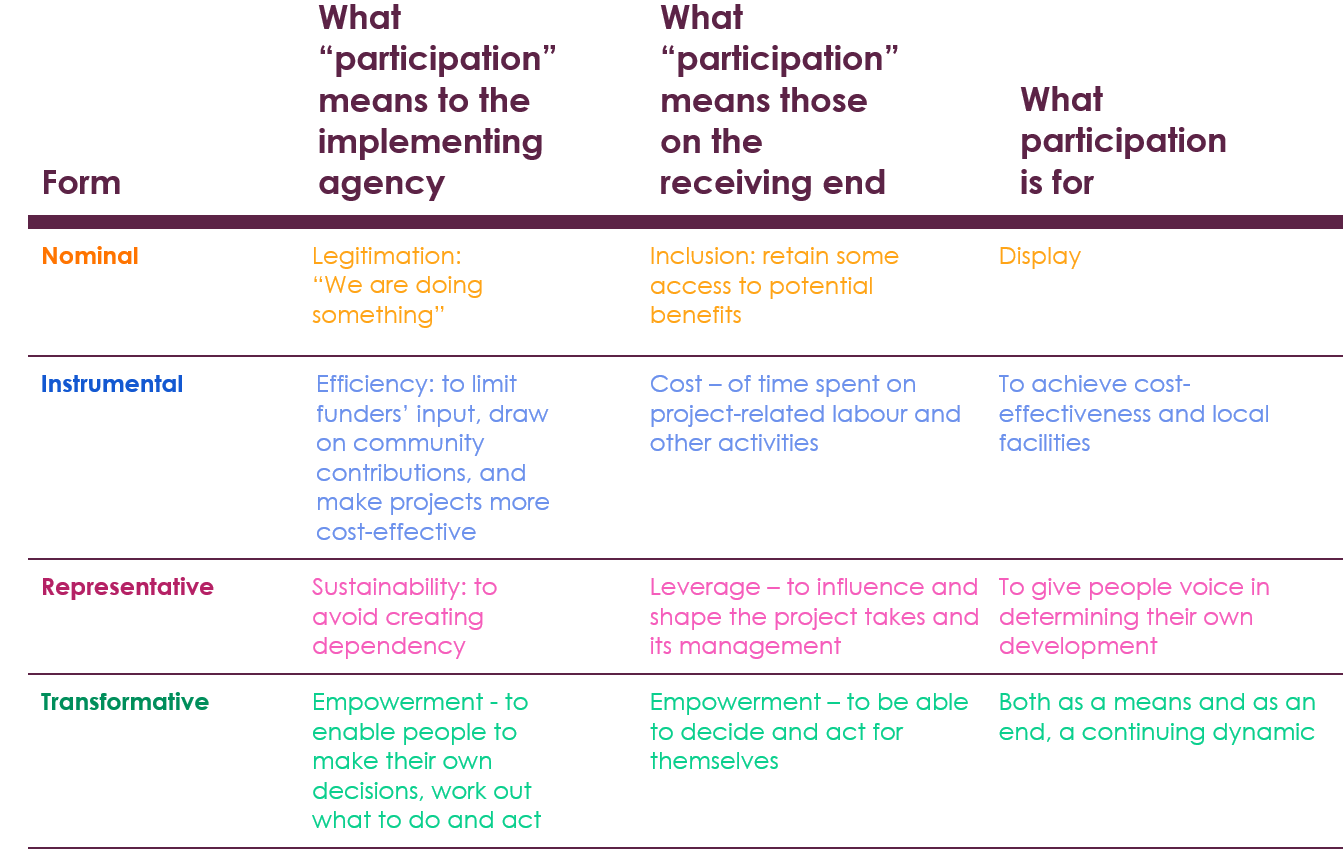

Relatedly, we’re rather fond of Sarah White’s matrix from 1996 which, like Sherry Arnstein, helps describe different levels of participation so we can tell what good looks like. In this case, though, Sarah White’s matrix tells the story of what might be going on out-of-sight. What might the motivations of different actors be? And what does that tell us about their values?

In White’s matrix, the ladder is upside down. Nominal participation is worst, and transformative is best.

If you think of an organisation, you’re familiar with, where would they be on this matrix?

What do you think about that?

If you want to geek-out on ladders and matrices of participation, here’s a great place to go.

Some Essential Ingredients

While there is not a single recipe that can be applied everywhere at every stage, there do seem to be some recurring principles and values that appear whenever democratic money has been tried.

In particular, we have noticed a core belief in participation and empowerment, a commitment to justice, and unconditional respect and trust for people with lived experience are all essential to bringing about positive change.

A belief in participation and empowerment

Shifting power from resource-holders to resource-users requires a belief in the autonomy and sovereignty of communities making decisions about issues that affect them. These kinds of values seem to translate into real power being given, not lent, to communities. For example, Camden Giving’s Board has never overturned a decision of its participatory grant-making panel because it didn’t like it.

Some interesting examples are: The Edge Fund, Camden Giving, and Islington Giving.

A commitment to justice

Freedom, fairness, legitimacy, truth… there’s a lot going on in the word justice. In democratic money, it seems to read as the right of communities to hold the power of decisions. Solidarity, not charity, is what communities seem to be asking for: the latter, they often feel, is culturally loaded with saccharine gratitude for something they should always have had anyway.

Some emerging examples are: The Big Issue Group, Fair by Design, and the examples in the Grassroots Grantmaking report.

Unconditional respect and trust

Part of the definition of marginalised communities is that they are too often unheard, and not given the trust and respect they have earned through lived experience. Assigning proper value to communities and their knowledge seems to be a non-negotiable part of respect and trust. At their best, examples of democratic money use this to adapt and learn how to make better decisions from different ways of knowing.

Some intriguing examples are: The Corra Foundation, Two Ridings Community Foundation, and the Tamarack Institute.

Liberating talent with (un)learning

The argument that communities are not expert enough to make complicated decisions about money is part of marginalising them. It even creeps into the corners of charity guidance. It turns out this fear is evaporated by the best examples of democratic money, by returning to what makes an expert: learning and experience. Putting resources into sharing the tools and knowledge of money with communities liberates their talents and elevates their expertise.

An example of learning and unlearning is: Democs (the deliberative democracy card game).

Rational Apathy [excuse me, what?!]

Here’s a curious thought.

Isn’t it just perfectly rational that people have disengaged from the process of making social or financial decisions, but are increasingly furious about the ones that get made in their name?

If, on the one hand, it is going to take you some time, effort, and opportunity cost to learn about the issues that need solving and, at the same time, the processes you see all around you tell you that your voice and your vote probably won’t make any difference, what’s the rational, logical, response to that? To disconnect, isn’t it?

Democratic money, at its best, recognises the truth of this whilst keeping hope alive for change, by doing two things: keeping its promise that the integrity of the process is non-negotiable; and helping all of us reengage by relearning how to be good public citizens as well as good private citizens.