Heroes and Villains in Systems

Systems don’t really do simple.

They do complex, non-linear, emergent, adaptive behaviour.

Our species finds that hard to deal with, so we typically find humans trying to simplify the complexity.

Hardly a month goes by without someone asking if we could just summarise a complex system in five bullet points (you’d be surprised how often it’s five), or we hear a tale of systems that has heroes and villains in it because that makes the story simpler.

This need to simplify things is because there are humans in the system. And that got us thinking.

What if we could unlearn our need to simplify systems and stories?

What if, instead of making systems come towards us by simplifying them, we moved towards systems by getting more comfortable with complexity?

What if, instead of our tales being cast with heroes and villains, we re-cast the stories with different characters?

What if the humans weren’t the problem at all, but the design of the system, and the incentives built into it, were?

Let’s rewind for a moment to remind us why these things might be important.

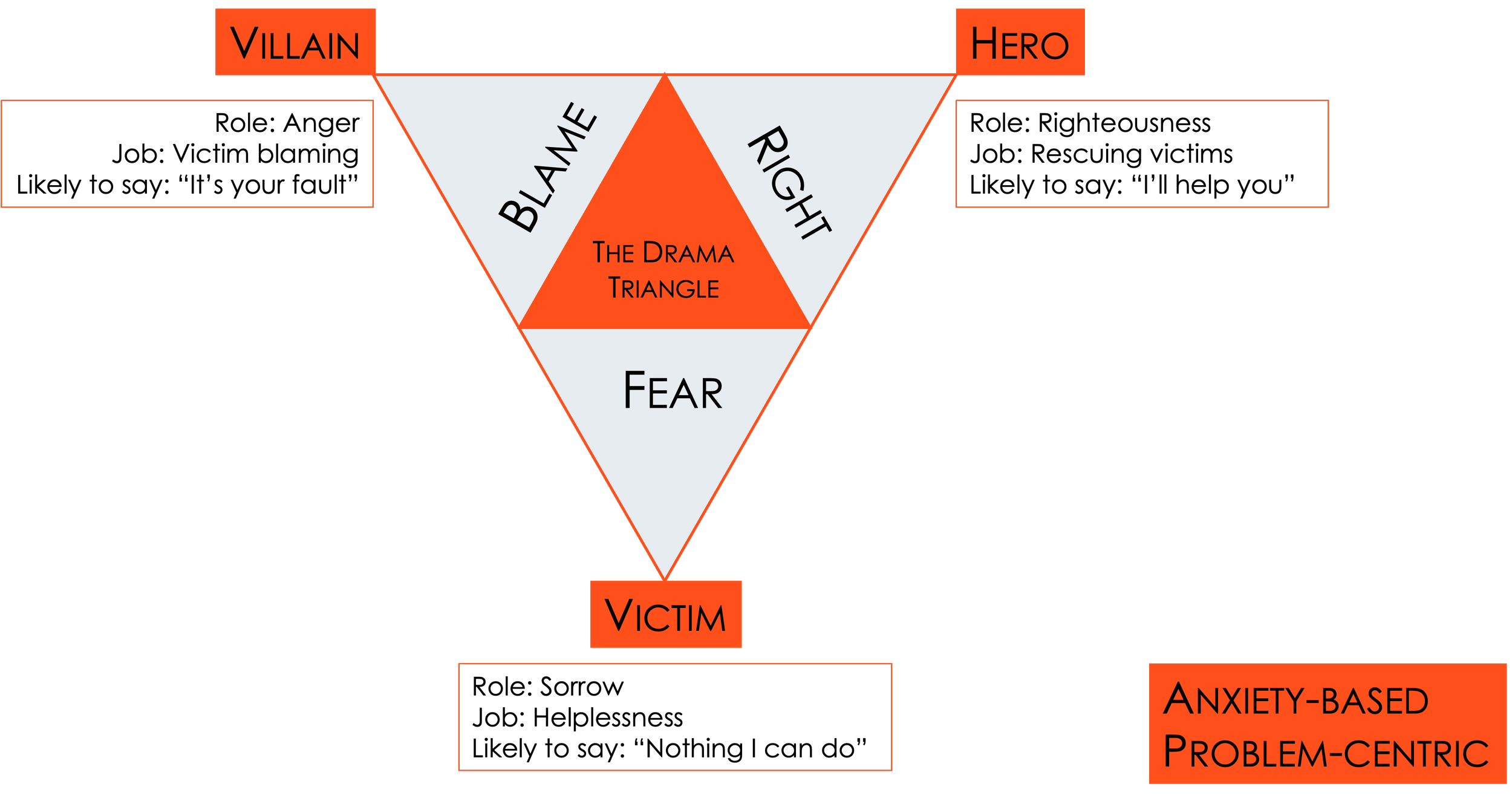

The social sector of charities and social enterprises has always been a moral space, trying to do the right thing by repairing the social and environmental damage we do to ourselves in other parts of human society, like politics or economics. Because of that, perhaps it’s no surprise to find charities and social enterprises casting themselves in the role of heroes in the drama, saving victims from the villains in the world. It's a way of simplifying the story we tell ourselves. A drama triangle played out every day in the theatre of society:

This kind of character casting shows up in another kind of triangle too: the three voices that go alongside Bill Sharpe’s three horizons model for thinking about how systems change with time.

This time, the casting isn’t heroes, victims, and villains; it’s incumbents (horizon 1), imagineers (horizon 3), and innovators (horizon 2) [that is: the people that inhabit the current system, the visionaries who are imagining a completely new system, and the change-makers that are building the new reality in between the old and the new]. It’s another way of simplifying the story we tell ourselves. In this version of the drama, the people in each horizon have a particular voice (loud!), and a particular way of hearing the others (tone-deaf!):

Looked at through the lenses of drama triangles and three voices: the polarising, judgmental, dehumanising, identity politics and culture wars of the early 21st Century definitely look triangle-shaped don’t they? We’ve even elected governments on the basis of ‘not that’ (the incumbent system) and ‘not them’ (the villains in our stories of what’s wrong with life).

But wait! There are other versions of these triangles. More hopeful. More helpful. More human.

The stories are still simple enough, but the cast of characters are more complex: just like the systems they are trying to understand.

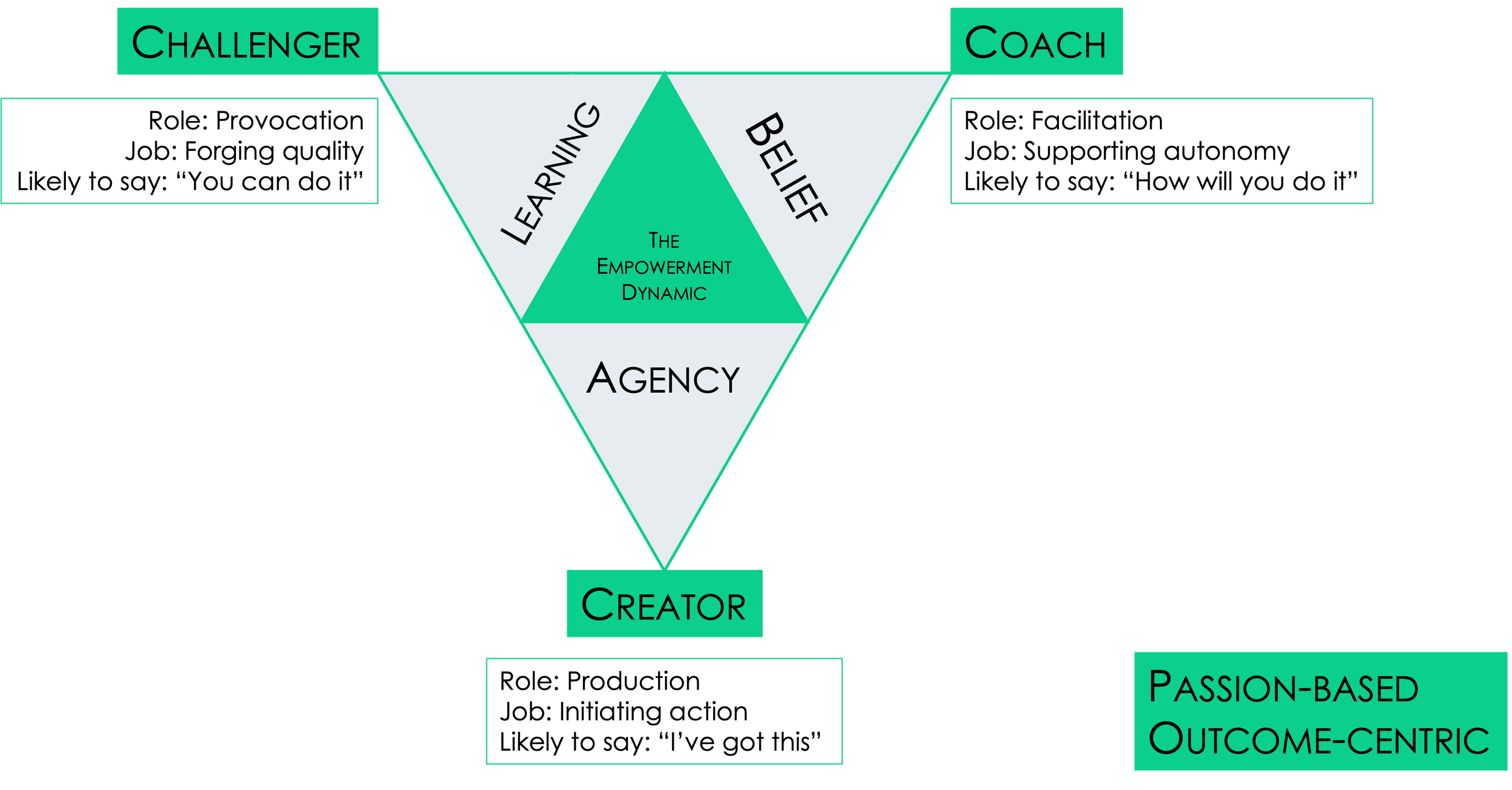

In the social drama, the villains become challengers, the heroes become coaches, and the victims become the creators of their own future:

Notice the subtle switch?

What’s happened is that the characters, rather than being in love with their solution, have fallen in love with the problem. They have a common adversary in the story now: the system and the incentives that make it tick.

It's the same with the three voices triangle. By falling in love with the problem, the characters in our social story become interested in the challenges again, interested in conversations again, see one another as human again:

The message from both these models is the same: focusing on the problem, rather than on each other, can release a colossal amount of energy to make systems better.

Maybe if we put all that energy into re-wiring the systems that are so broken, instead of shouting at each other about who’s fault it is, we could mend them a whole lot faster?

Imagine a healthcare system that asks not what’s the matter with you, and has incentives designed to solve for that with eligibility tests, queues, and financial rationing; but asks what matters to you – and then re-wires all the incentives to solve that with health promotion, prevention, resilience, and humanity.

Or imagine a housing system that asks not how much can I make, and has incentives designed to solve for property and profit; but asks how much do we need – and then re-wires the incentives to solve for people and planet with incentives for adaptability, affordability, equitability, and freedom. We’re working on this right now with the Nationwide Foundation.

Or imagine a financial system that asks not what can we take out, and has incentives to push all the risks and the costs onto clients and the climate; but asks what can we put in – and then re-wires the incentives to make money more society-shaped rather than bending society to be more money-shaped.

In any of these examples, did you find yourself saying ‘yes, but’ and then saying something about the characters in the drama? Not easy is it? We’re trying to un-learn that too, every day in our work on systems change, and stay focused on the design of systems and the incentives that make them tick.

For us, it’s made a big difference. Just the practice of de-centring the people and re-centring incentives has reminded us that there are rarely heroes and villains in the story of systems change. Just rational people trying to make the best of the system they’re part of.

It’s helped us fall in love with systems change all over again.

Maybe it’ll be the same for you.