What hope is there for hope?

Whenever we’re working with clients on systems, we’ve noticed that, at some point, hope joins the meeting.

Sometimes it’s a little late. Sometimes it comes in disguise, so it’s hard to spot at first. Or it just sits quietly at the back and doesn’t say much. But it’s always there.

We often wonder that, if hope is in disguise, or keeping quiet, how do we even know it’s there? What does hope even look and sound like anyway?

Interesting question that. And, it turns out, a vital one if we’re going to change the systems that are serving us so badly right now.

In working on changing systems, we’ll often begin with seeing the system you want to change (because it’s hard to change something you can’t see), and then move into describing what’s wrong with it and why it’s failing. Hope hasn’t usually turned up to the meeting yet. But then something happens: the people in the room realise that it’s not enough to say what they don’t want. If they’re going to make any progress, they need to say what they do want.

And that’s when hope joins the meeting.

If we’re working with clients on a theory of change, for example, using our very own Transformational Index card game (other tools are available!), the indicators our clients pick are an embodiment of their hope for a better future.

Building a systems-centric theory of change (not a linear, logic model, because the real world is neither linear, nor logical !)

Or if we’re intentionally working on the 3 Horizons of systems, it’s when we get to Horizon 3 that our clients pause, and then describe the future they want to see, with hope.

Hope, though, is not wishful thinking. Neither is it optimism. Nor a fantasy. Nor escapism.

What then, should we say that it is?

It feels to us like a powerful moral and existential place. A dream of transformation, and the conviction to act with courage to change things. It feels purposeful.

As the philosopher Kierkegaard might have said, hope is not wishing, but willing. Or, if you’re a fan of a different philosopher, Kant's argument is that that hope motivates ethical action, which is a near-perfect description of the hopefulness that underpins the entire social sector. Not as a way of sweeping up the broken people and pieces of the planet created by our current self-destructive systems. But as intentional, defiant, active hope that knowledge, action, and moral clarity can change the course of history.

One of our favourite descriptions of hope is from the 4th Century AD and Augustine of Hippo who is said to have written:

“Hope has two beautiful daughters. Anger. And Courage.”

Which feels very much like a heady mix of protest and purpose. More prophecy than fantasy. What it certainly is not, is passive.

Hope feels like it’s having a hard time right now. It feels like we’re in something of a hope recession. Climate change, rising authoritarianism, economic self-destruction, and technological (existential) anxiety seem like they could get the better of hope.

And yet, hope is paradoxical. It seems that the more the world tries to oppress it, the more irrepressible it gets.

Vaclav Havel, the Czech dissident and president, describes hope as a way of living truthfully even under oppression. An “orientation of the spirit,”. Listening to the choral expression of hope in Arnesen’s Even When He Is Silent, itself a song of the text carved into a cellar wall by Jews fleeing the Nazi’s in Cologne, captures the beauty and the defiance of hope: I believe in the sun, even when it’s not shining; I believe in love, even when I feel it not.

In a world saturated by cynicism, fear, and distraction, hope deserves to be nurtured, and chosen. It demands imagination and endurance. Hope is, in the words of Mariame Kaba: “A discipline.” And it’s a powerful one, driven by a version of the future that doesn’t just recoil from what is, but pulls us towards what could be.

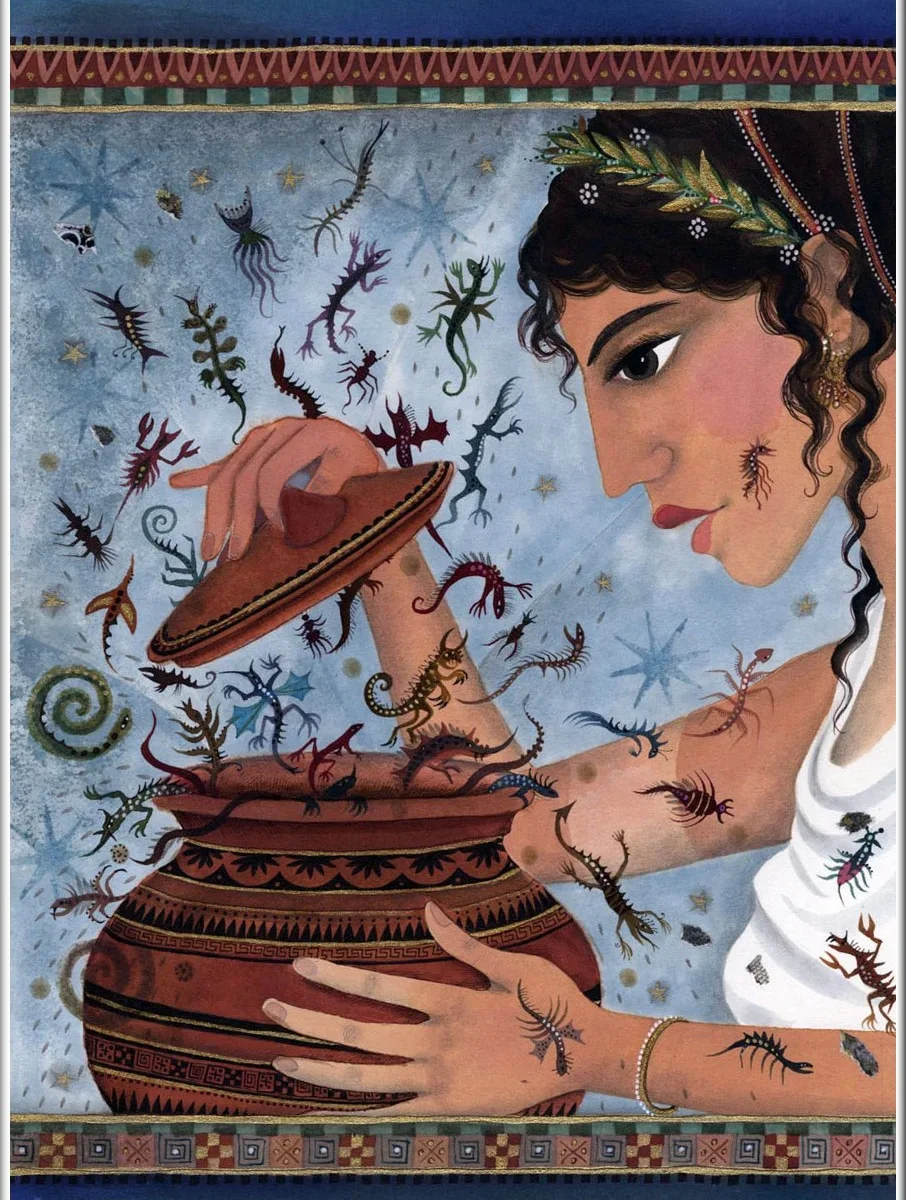

When the world feels like humanity has opened Pandora’s box of self-destruction, it’s worth reading the story of Pandora again from Greek mythology: As a vengeful wedding present, Zeus gave the first woman on Earth, Pandora, a pithos (a kind of jar, now described as a box) that came with strict instructions not to open it. It was designed as a punishment to Prometheus for stealing fire from the gods and giving it to humans. For Pandora, who was created curious, the temptation was irresistible, and she opened the lid. What poured forth into the world were all of life’s miseries: greed, envy, hatred, pain, disease, hunger, poverty, war, and death.

Pandora slammed the lid shut; but too late.

When she looked again, the box was empty…

Except for one thing that remained.

One thing for Pandora to hold onto after releasing life’s miseries into the world.

That one thing, was hope.

Next time you’re gathered with your colleagues or friends, see if you can see and hear hope in the room.

And if you can’t, maybe open the door and let hope join the meeting.